In the

wild, all

hosta species have the ability to reproduce by

seed but some are more prolific than others. Hostas are

in the group of plants that have

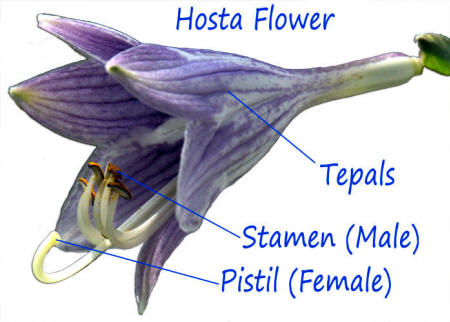

perfect flowers. That means that they have both male

(stamen) and female (pistil) reproductive organs in the

same flower. Therefore, seeds can develop through

fertilization with pollen from the same plant i.e.

self-pollination a.k.a. selfing, or pollen from another

plant i.e. cross-pollination.

Either

way, the resulting seed will be the mixture of two

different sets of genetic material. This variability

means that the offspring i.e. seedlings, may have some

unusual or new traits not exhibited by either parent.

That fact opens the way for discovering a new cultivar

among a group of seedlings. Gardeners, hybridizers and

nursery people use this characteristic of plants in two

ways:

_ A. Let Nature Do the Job

- A certain number of new hosta cultivars are simply

"found" in the garden or nursery. Hostas are generally

pollinated with the help of bees. The insects get up

early in the morning, buzz around the newly opened hosta

flowers and carry pollen from one to another. So, in the

case of these random acts of nature, you might know the

name of the mother plant from which the seeds were

gathered but you won't know the name of the father or

pollen parent. If the seedlings just sprouted up where

the seeds dropped the previous fall, you wonít know the

name of either parent for sure.

Extremely knowledgeable

hostaphiles like

Mark Zilis,

Bob Solberg or

W. George Schmid might be able to make an educated

guess as to the parentage based on physical traits but

it would only be an opinion. I suppose with today's

technology, we could do a DNA analysis and might be able

to figure it out but that would be very expensive. Maybe

in the "Star Trek" future, we could just wave our cell

phone at the plant and a free app we download from the

internet would determine the plant's genetic background.

Who knows? Anyway, these types of cultivars are called

open-pollinated and are often registered as "parentage

unknown".

_ B. Get People Involved

- Of course we humans have a burning desire to get

involved and control nature if we can. So, since the

time we learned the mechanics of how plants reproduce,

we have been manipulating the plant world through a

process called hybridization.

Hybridizing generally involves the combination of the

genetic materials from two different plants. For this

cross-pollination to work, of course, both plants need

to be in flower at the same time. Often, hybridizers

take the pollen from a plant and place it on the pistil

of the same plant which is called self-pollination or

simply, selfing.

The

whole idea of a person going out into the garden to

collect pollen from one plant and putting it on the

pistil of another is to try to combine the good traits

of each while de-emphasizing the bad traits.

_

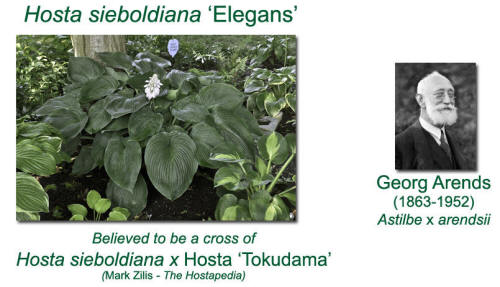

1. History of Hosta Hybridizing - It appears

that gardeners and horticulturists in the hosta native

lands of

Japan, Korea and China may have been selecting

open-pollinated plants or manually hybridizing hostas

for a long time before Europeans came on the scene.

However, one of the early documented cases of

hybridization of hostas in the West was done by

Georg Arends in Germany. He is best known for

hybridizing astilbes (Astilbe

x arendsii), but Arends also introduced

perhaps the all-time classic blue cultivar, Hosta

sieboldiana 'Elegans'

in 1905. It is thought to be the result of a cross

between

Hosta sieboldiana x H.'Tokudama'.

Mr.

PGC Comment: By the way, the proper way to show the

plants involved in a cross-pollination is to list the

mother plant i.e. pod parent first, followed by a cross,

x, and then the father plant i.e. pollen parent, second.

For example, H. sieboldiana x H. 'Tokudama'.

When talking about this cross it would be spoken as,

"Pod parent, H. sieboldiana, by pollen parent, H.'Tokudama'."

Another

early hybridizer of renown was Eric Smith who lived in

Dorset,

England. A nurseryman who was then working at

the famous

Sir Harold Hilliers Nursery called Buckshaw Gardens,

Smith was looking to develop smaller hostas with great

blue color. In the summer of 1961, he took advantage of

a fluke occurrence when a plant of Hosta sieboldiana

'Alba' bloomed unusually late one summer so he could use

its pollen to fertilize the flowers of an H.'Tardiflora'

plant.

The

whole story of Smith's hostas gets a little complex but

suffice it to say, that his original cross spawned a

whole

series of smaller, blue-green plants commonly called

the "Tardianas". The seedlings of the first cross where

designated as the F1 generation and the second

generation plants were the F2s. This was part of Smith's

numbering system where he simply named a plant TF1 x 1,

TF1 x 2, etc.

Smith

himself did not register any of his 34

Tardiana hostas. Fortunately, other people including

Paul Aden,

Alex J. Summers and the British Hosta and

Hemerocallis Society named and registered the plants on

Smith's behalf starting in the mid-1970s. Of course,

many of the plants have the word "blue" in the name such

as H.'Blue Moon', H.'Blue Skies', etc. Others have the

term "Dorset" in the name including H.'Dorset Charm', H.'Dorset Flair', H.'Dorset Blue' etc. Finally, the

term "Hadspen" such as H.'Hadspen Heron', H.'Hadspen

Hawk' and H.'Hadspen Pink' appears in this line of

hostas.

Mr.

PGC Link:

_

2. Goals of Hybridizing - Hybridizing hostas may

be as simple as wandering around your garden, collecting

some seeds and growing them to see what you get.

However, for most people who call themselves

"hybridizers" it is a much more thoughtful process. They

set goals that they want to achieve in their programs

and work consciously toward making those goals a

reality.

Generally, the hybridizer will choose one or more

specific traits that they would like to "improve" and

pick pod and pollen parent plants accordingly. They may

try to create a "bluer" blue hosta or one that has

fragrant flowers or better leaf substance on a highly

variegated, thin substanced cultivar. While creating

changes, they may desire to keep certain characteristics

such as leaf shape, flower color, bloom season or plant

form unchanged. As mentioned before, you want to

accentuate the desirable traits while minimizing or

eliminating those that are not desirable.

All of

this sounds so simple and straightforward but in the

world of genetics, it can be quite a challenge. Just ask

any hybridizer how many times they are successful in

their quest and most will say they are lucky if one

plant in hundreds of seedlings shows real promise.

_

3. Approaches to Hybridizing

_

a. Open Pollination - As discussed

earlier, you can simply let nature do its thing and see

what happens. Randomly collected seeds will be

considered open-pollinated since you have no idea where

the pollen originated. It is believed that in many

cases, the pollen comes from the same plant as the bees

brush up against the stamen and then crawl over to the

pistils. That would make seeds from these plants not

"technically" hybrids since all the genetic material

came from the same plant. However, the resulting

seedlings may still have some variable traits.

The

only hostas that come perfectly true to type from seed

are plants of the species, Hosta ventricosa. In a

process called apomixis, seeds are formed in an

asexual way (does not require the mixing of pollen onto

the pistil) that results in exact genetic copies of the

mother plant. Strange but true.

_

b. Line Breeding - This is a process

where plants that are closely related are bred to each

other. For example, you might take the pollen from the

seedling of a mother plant and use it to pollinate the

same mother plant. The intention of "inbreeding" is to

isolate certain traits that are recessive and may

express themselves during this process. By continuing

the line breeding route over several generations, the

hybridizer is hoping to either accentuate or eliminate a

specific trait or traits.

_

c. Cross Breeding or Outbreeding -

Cross-breeding occurs when you take the pollen from a

father plant and transfer it to the pistil of an

unrelated mother plant. The idea here is to take a plant

with a desirable trait and add that trait to the mother

plant. Or, it could be to eliminate an undesirable trait

from the mother plant. Perhaps the mother plant has

roundish leaves and you cross it with a plant that has

narrow leaves in an effort to reduce the leaf width.

_

d. Self-Pollinating or Selfing - As

the name implies, this process takes the pollen from a

plant and applies it to the same plant's pistil. The

desired outcome is often that the seedlings may show

enhanced characteristics of the mother plant through

expression of genetically recessive traits.

_

e. Combinations - Of course in their

never ending quest for better hostas, hybridizers will

sometimes have to resort to using combinations of these

techniques. They may start out by line breeding a

particular plant and then finish by crossing it with a

separate cultivar or species plants to see what results.

It can be an involved and fun game.

_

4. The Hybridization Process - As described

earlier, in order to produce seeds, pollen from the male

organ (stamen) must somehow reach the top of the female

organ (pistil) and then travel down into the ovary to

fertilize the eggs. In the hosta garden, this is

generally done by bees, but humans can easily do the job

too.

We can

describe the basic procedures here and that will give

you an idea of what is involved in hosta hybridizing.

However, as with any biological process, there are

always exceptions and subtle "quirks" that cause

problems or create opportunities for the hybridizer.

Learning to effectively deal with these unique

situations is what keeps hybridizers working on the

process for years while they discover new things about

hostas. There are even several organizations of people

devoted to hosta hybridizing where members share their

techniques and solutions to problems they encounter.

So,

here is the basic process that you can use to give

hybridizing a try.

_

a. Identify two hostas that are in bloom

at the same time in your garden. You could do this

randomly or, as we discussed, you can isolate a specific

trait or traits in each plant that you want to impact in

some way through your cross.

_

b. Like

daylilies, hosta flowers only

bloom for one day. They begin to open around 3 a.m. and

should be fully open well before sunrise. This means the

pollination process needs to be completed in one outing

for any particular flower since it will shrivel and fade

away if it is not pollinated that day.

_

c. The next step is to make sure that

bees do not pollinate the flowers before you do. There

are several ways of accomplishing this task. The tepals

(petals plus sepals) of the flower are what attract the

bees, so one approach is to go into the garden around

sunrise and gently strip them from the flowers of the

mother plants. Also carefully remove the stamens

(unless you are doing a self-pollination) leaving only

the pistil exposed.

If the

flower has been prepped properly, the pistil will be

slightly curved upward and the top end i.e. the stigma,

will be enlarged. Pistils that are straight up and down

with no curve are not ready to be pollinated and you

might need to go through the process again the next day

on that plant...and, of course, on a new flower.

Another

approach is to somehow cover the flower so that bees

cannot get to it. On plants in the shade, you can simply

put the flower into a plastic bread bag secured with a

tie down. In sunny situations where the flower may "fry"

under plastic on a sunny morning, you can use some very

fine mesh netting to cover the flower. Mosquito netting

type material should work fine.

_

d. Many hybridizers recommend collecting

the pollen from the father plant well in advance of

making the cross. If you wait too long, the bees may be

active and might have disbursed all the pollen before

you get to it. Complicating the process is that the

pollen needs to warm a bit in order to "ripen" properly

and this may not happen until well after sunup in the

garden.

You can

go out the night before making your crosses and remove

the stamens from unopened flowers of your selected

father plants. Be sure to have a system for keeping

track of the name of the plant where each stamen

originated for your records.

When

collected in this way, the stamens will have no yellow

color. Store them overnight in a warm, dry place and, by

the morning, they should be covered with a fluffy yellow

powder...the pollen. If this has not happened, you can

try gently warming the anthers to promote the pollen

formation. Be sure to keep stamens from different plants

physically separated from each other to prevent

contamination.

_

e. Later in the morning when the air

temperature has increased, it is time to actually apply

the pollen to the pistil of the mother plant. There are

several methods for transferring the pollen but the key

is that you must be very careful not to mix pollen from

two plants. This would mess up the whole process.

One

approach is to take several clean, small paint brushes

with you into the garden. That way, you can use a

different one for each of your crosses to avoid

contamination. Brush the stamen of the pollen parent and

then apply the pollen to the top of the mother plantís

pistil. When you are done, be sure to thoroughly clean

all the brushes before your next round of hybridizing.

Another

common approach is to actually remove the stamen from

the pollen parent and, using a pair of tweezers, move it

over to the mother plant. Gently rub the top of the

stamen onto the top of the pistil to make the transfer.

Be sure to thoroughly wipe off the tweezers between

crosses to avoid contamination.

If you

really get into hybridization, you will hear about many

other techniques for transferring the pollen. Some of

them are very inventive...and some are just a little

strange but it does not matter as long as the method

works and viable seed is produced.

_

f. One of the key elements to successful

hybridizing of hostas is to keep accurate records of the

parent plants used in each cross. To do this, you MUST

keep detailed records all the way from the day the cross

is made through growing the seedling onward for 5 or 6

years. Lost or inaccurate labels are the bane of

hybridizers' lives.

Immediately after you make the cross, you need to have a

method for labeling the mother plant and the seed pod

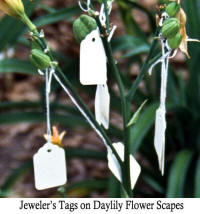

that will (hopefully) develop. Many hybridizers use

jeweler's tags which can be filled out in the house the

night before and then tied onto the flower stem when the

cross has been made. Use a fine tip, UV resistant pen to

assure that the label will be readable at the time of

harvest a month or more later.

Since

the space on the label is limited, you will have to

develop your own coding system. The key here is to write

everything down and to make multiple copies of it on

paper and in your computer. It is awful to come to some

point in the long hybridizing process, look at a label

that says, "LY3-t788-012" and have no idea what that all

means.

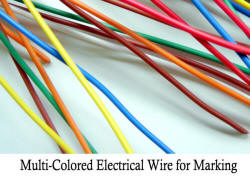

Another

approach to identifying seed pods is to use small pieces

of electrical wire. These are available in many

different colors and you can come up with a system using

different combinations. For example, twisting two pieces

of yellow, one of red, two of green and a single blue

wire on a seed pod may stand for H.'Sum

and Substance' x H.'Blue Moon' made in the fall of

2012. Again, keep good records and keep multiple copies.

_

g. If you were successful in your efforts

in hand pollinating, a seed pod should begin to develop

within about 4 or 5 days. This will begin with a

swelling at the base of the pistil where the ovaries are

located. If the cross did not "take", the ovary will

turn yellow and drop off the plant. A pod with viable

seeds in it will be firmly attached to the stem and will

not fall off by being shaken by the wind or when you

pollinate another flower on the same stalk later in the

bloom period.

Mr.

PGC Comment: Don't automatically assume you did

something "wrong" if the cross does not work. Hostas are

notorious for being unpredictable when it comes to

setting seeds. It could have been high temperatures, low

humidity, dryness and other factors out of your control

that caused the failure. Or...it could have been your

poor technique...sorry.

_

h. It takes about 30 days after

pollination for hosta seeds to develop to maturity or

"ripeness". That is why certain hosta species such as

those which flower very late in the season are quite

difficult to hybridize in northern gardens where frost

hits before seeds have had time to mature. For most

hostas in the northern climates, this means that any

crosses made after Labor Day will probably not bear ripe

seeds unless warm weather persists.

_

i. Harvest the seeds when they are

mature. Although most people wait until the seed pods

have turned brown, the seeds within may actually be ripe

prior to that time. Mature seeds will be dark brown to

black in color with a single "wing" on them. These may

be harvested and either planted immediately or may be

kept for later planting. Put the seeds in a properly

labeled paper envelope and place them in the freezer if

you plan to keep them for an extended time before

planting.

_

j. Since hosta seeds do not have to go

through a "chilling" process like many other perennials,

hybridizers often plant their seeds indoors under

fluorescent light systems immediately after they are

harvested. Many keep the lights on for 24 hours a day to

push the growth of the seedlings at an accelerated rate.

_

k. Once the plants are growing on their

own, the time begins for perhaps the most difficult part

of the whole hybridizing process. After the seedlings

develop their third set of leaves, most hybridizers

begin the "culling process". This means that they start

pulling out and discarding any and all seedlings that do

not appear to meet their hybridizing goals. It sounds

cruel and, seems wasteful, but often over 99% of the

seedlings you produce will end up in the compost bin as

you search for that one special plant.

You

will probably want to set up some type of schedule for

your culling process. Some people cull in the spring and

then again in the fall while others pull out plants

whenever they happen to wander through the seedling

patch. Remember that you can always eliminate a plant

later but, once you have tossed it into the compost bin,

it is for all intense and purposes gone forever. So,

when it doubt, leave it alone.

Mr.

PGC Comment: Over the years, I have heard at least

one story of a visitor plucking a rejected seedling from

a hybridizer's compost pile and discovering what turned

out to be a very nice, new hosta cultivar.

_

l. Keep up the culling process for

several growing seasons until you have (with luck) a

plant or two that meet your goal(s). Watch that unique

hosta grow until 5 or 6 years after the seed was sown to

be sure that it is a plant worthy of introduction as a

new, named cultivar. Or, use it to continue your

hybridizing process.

That,

in a nutshell, is hosta hybridizing. As we mentioned

before, it can be just this or so much more depending on

how far you want to get into it. Hybridizing is a

wonderful way to keep learning and growing in your

knowledge of this great landscape perennial.

_ 5.

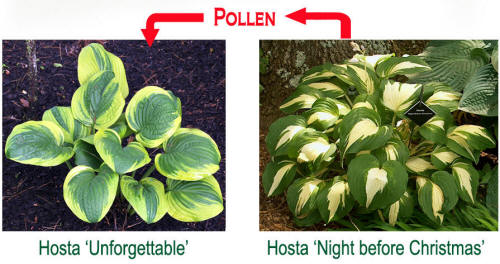

Variegated Seedlings - Hosta 'Unforgettable' is a

variegated plant with a blue-green center and

yellow-gold margin. Hosta 'Night before Christmas' is

variegated with a white center and green margin. If you

took the pollen from one (the father plant) and put it

on the pistil of the other (the mother plant), what

color seedlings would result? Would they have green or

white centers? Would their margins be green or gold or

some mixture of all of these colors?

The

answer is that the seedlings would all be plain old

green or blue-green. Surprised? Well, the reason is that

(with one exception that we will discuss shortly), the

variegation on hostas is not a genetic trait. As

explained in the section on variegation, it is just a

change in the physical makeup of the pigment cells in

one or more of three of the many layers of leaf tissue.

Mr.

PGC Comment: I have a small birthmark on my arm that

is slightly reddish in color. This is just a change in

the pigment in my skin in that spot and is not part of

my genetic makeup. Therefore, it will not be transmitted

to my children. It is generally the same situation with

the variegation in hostas. There is a tiny, tiny

possibility that a genetic mutation might take place

resulting in the rare variegated seedling under these

hybridizing circumstances. Somewhere I heard the odds of

that happening are less than 1 in 10,000. Also, yes, the

"before" in H.'Night before Christmas' is not

capitalized for some reason.

So, how

do hybridizers ever produce variegated seedlings? Well,

as mentioned above, there is one exception to the rule.

That occurs when the mother plant has splashed or

streaked variegation in its foliage.

If you

ever go to an auction at

The American Hosta Society convention, you will see

plants with streaked variegation being sold for some

very high prices. The reason is that hybridizers need

such plants to act as mother plants in their search for

variegated seedlings. They will spend hundreds and

hundreds of dollars to acquire streaked plants that have

other characteristics such as size, base color, leaf

shape, flower color, red petioles, etc. that they want

to work into their breeding programs.

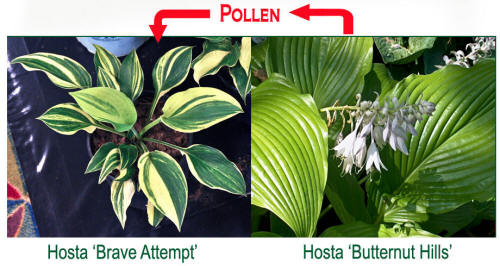

So, if

the hybridizer takes pollen from an all green father

plant such as H.'Butternut Hills' and places it on the

pistil of a streaked mother plant such as H.'Brave

Attempt', he or she will generally get a mixture of

solid, variegated (marginal or medial) and streaked

seedlings. Each seedling will have some of the genetic

characteristics of each parent and there might be one

that deserves to be introduced as a new, variegated

cultivar...or perhaps not.

The

unpredictable (and perhaps expensive) part of all of

this is that the variegation on most streaked plants is

notoriously unstable. There is a chance that next spring

when that streaked plant you paid so much for emerges

from the ground, it may have reverted to a single color

or to a non-streaked form of variegation i.e. marginal

or medial. If that happens, it will no longer produce

variegated seedlings and is just another hosta.

Mr.

PGC Comment: Remember that not all streaked

cultivars are so unstable. Some like H.'Spilt Milk'

remain the same for decades and may only occasionally

have a single division or two that reverts.

_ 6.

Hybridizer Groups - Although some people take

hybridizing very seriously and may guard their special

techniques and knowledge jealously, most hosta

hybridizers are more than willing to share with others.

In many parts of the country, they have formed groups

dedicated to helping advance the science and practice of

hosta hybridizing for both the beginner and the expert.

If you are interested in participating in such a group,

the best way is to join The American Hosta Society and

your local and state hosta organizations. If there is a

hybridizer club functioning in your area, these groups

will surely know who to contact in order to join in the

fun.